Health care support worker Kormasah Deward smiles for a photo in Woodbury on Aug. 3, 2023. "You get an extended family, you know that you're changing the world, and you're putting a smile on another person's face," Deward said of being a personal care assistant. She was part of an SEIU bargaining team that won a large pay raise for PCAs. Photo by Madison McVan/Minnesota Reformer.

Damon Leivestad, a 50-year-old mechanical engineer with spinal muscular atrophy, has struggled to find personal care assistants for years.

Leivestad uses a wheelchair and needs help moving between his bed and wheelchair, getting dressed, and doing everyday tasks like shopping and food preparation.

His condition is deteriorating while his parents age, and hiring people to help him with everyday tasks has proved difficult even as it’s become more important.

“(My parents) take care of me, but my dad is 79 and my mom is 75, so it’s really difficult for them to do that now. And now I have fewer PCAs than I ever have in my entire life,” Leivestad said.

The problem is likely to worsen, economists and demographers say.

The demand for home health and personal care aids is expected to be higher than any other occupation over the next 10 years, according to data from the Minnesota Department of Employment and Economic Development. Home health care employment is expected to increase by about 25% over that time.

Meanwhile, these workers — whose clients rely on them to live independently — are among some of the lowest paid in the labor force. Many work multiple jobs to make ends meet.

State programs and a new union contract — which will give thousands of personal care assistants at least a 25% raise in 2024, plus more in 2025 — hope to attract more workers to the health care support professions.

The gap between demand and supply of health care workers is due in part to demographics, said Valerie DeFor, executive director of HealthForce Minnesota, a state-funded health care workforce development center housed at Winona State University.

Baby boomers are aging and developing more health problems. At the same time, birth rates have fallen dramatically over the past 50 years, a trend that accelerated during the Great Recession, leaving a shortage of people to do the work.

Aside from demographics, the shortage of PCAs is also driven by a public policy choice.

Pay for personal care assistants is governed more by state law and insurance companies than typical labor markets, and policymakers for decades chose to pay PCAs some of the lowest wages in the entire labor pool. Women, immigrants and people of color have long comprised a majority of the workers in the field.

In Minnesota, immigrants make up 27% of PCAs, more than double the rate of the state’s overall workforce, MPR reported this week.

There’s glimmers of hope on the wage front, however: The Service Employees International Union represents around 20,000 care workers in Minnesota, and until the most recent legislative session, SEIU members were making $15.25 an hour.

That translates to less than $32,000 per year, before taxes. Given Twin Cities rents of about $1,100 for a one-bedroom apartment, the people caring for the elderly and people with disabilities are barely scraping by.

Meanwhile, other lower wage workers are making gains. During the pandemic, hourly pay at fast food restaurants and other entry-level jobs caught up to, and in some cases surpassed that of personal care workers.

Kormasah Deward is a health care support worker with 12 years of experience, an associate’s degree and several certificates in health care occupations. Being a personal care assistant is rewarding, Deward said, but also physically and emotionally demanding.

Jobs in retail and food service are hard, Deward said, but they don’t have the same responsibilities as personal care workers — co-workers can pick up shifts, and they get regular breaks, she said. When a PCA is late or misses a shift, the stakes are high: Their client may be stuck in bed, unable to do anything, including going to the restroom.

Deward has gone to great lengths — including sleeping in her car when she couldn’t afford gas — to ensure that her client could get up and go to work the next day.

“It’s rewarding…Even when you leave your house and you’re having a bad day, you go to (the client), and they have a smile on their face because they see you. They know that you’re there, and they know that they can have a good day today,” Deward said.

Deward was part of the SEIU bargaining team that negotiated a contract guaranteeing a $20/hour wage by 2025 along with other benefits, like additional pay for care workers with experience and bonuses for staying in a job longer than six months.

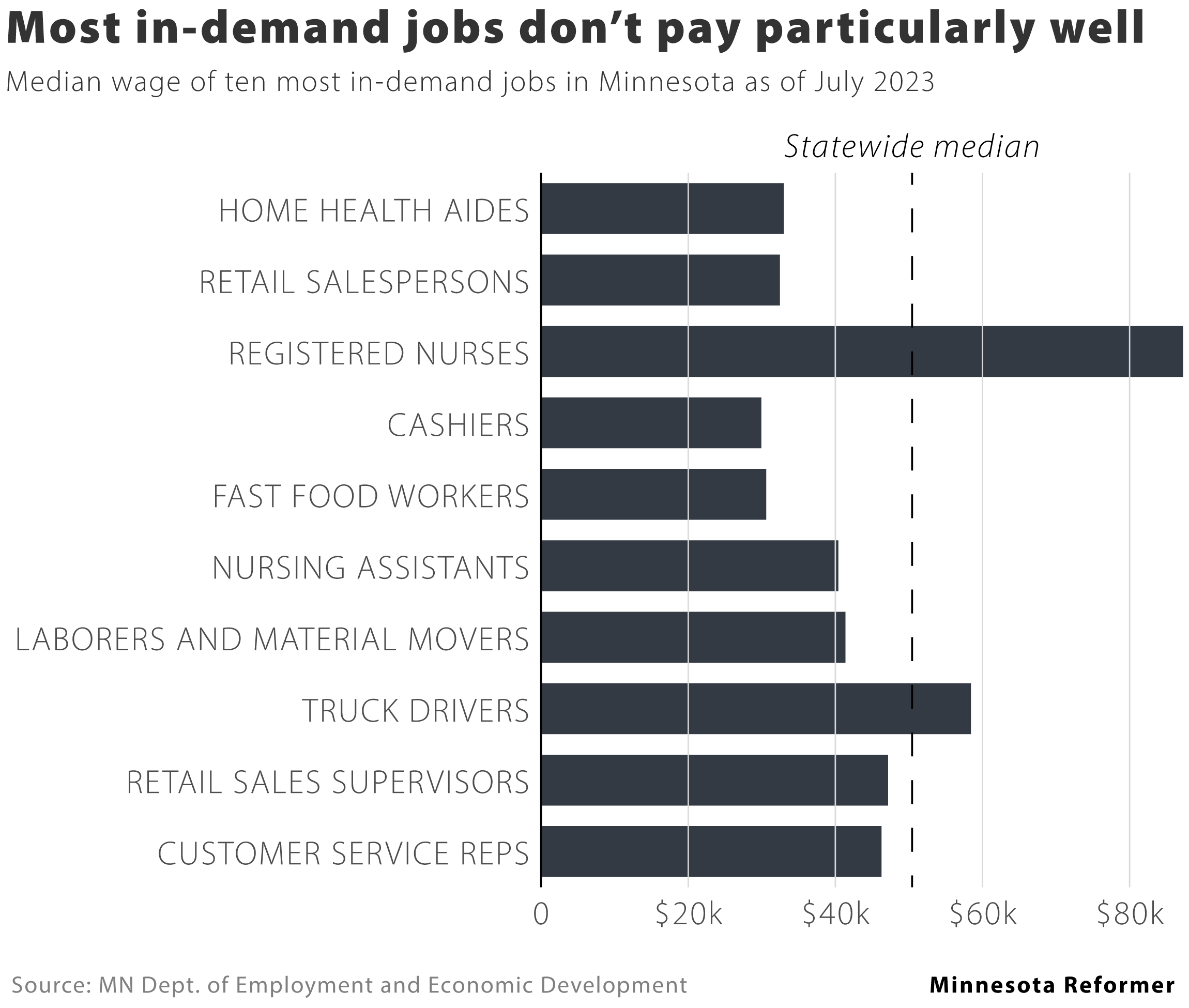

Low-paying jobs are in highest demand

The most in-demand jobs during the next decade are also often the lowest paying, according to the DEED data.

Home health and personal care aides are in the highest demand, followed by retail workers, registered nurses and cashiers. Eight of the top ten in-demand jobs require no education beyond a high school degree.

Four of the top five in-demand occupations have a median wage at or below $33,000 per year. Registered nurses are the exception, with a median income of around $87,000 per year. The nursing shortage was exacerbated by the pandemic.

The Great Resignation that occurred in the first year of the pandemic — when people left their jobs for higher-paying positions — drove up wages, particularly among the lowest-paying jobs.

That makes it harder for Leivestad to find help. He currently has one full-time personal care assistant, but she goes back to school in September and will have to reduce her hours by at least half. He regularly posts his job listing on more than a dozen Facebook pages, but has found that the current salary just isn’t enough for most people.

Leivestad interviewed a candidate recently who seemed like a great fit — but the pay was too low for him to take the job.

Leivestad told him next year, pay will start at $19/hour. That wage would be acceptable, the candidate replied.

Leivestad plans to circle back to that candidate in January.

The post Home health care workers among most in-demand Minnesota jobs — and lowest paid appeared first on Minnesota Reformer.